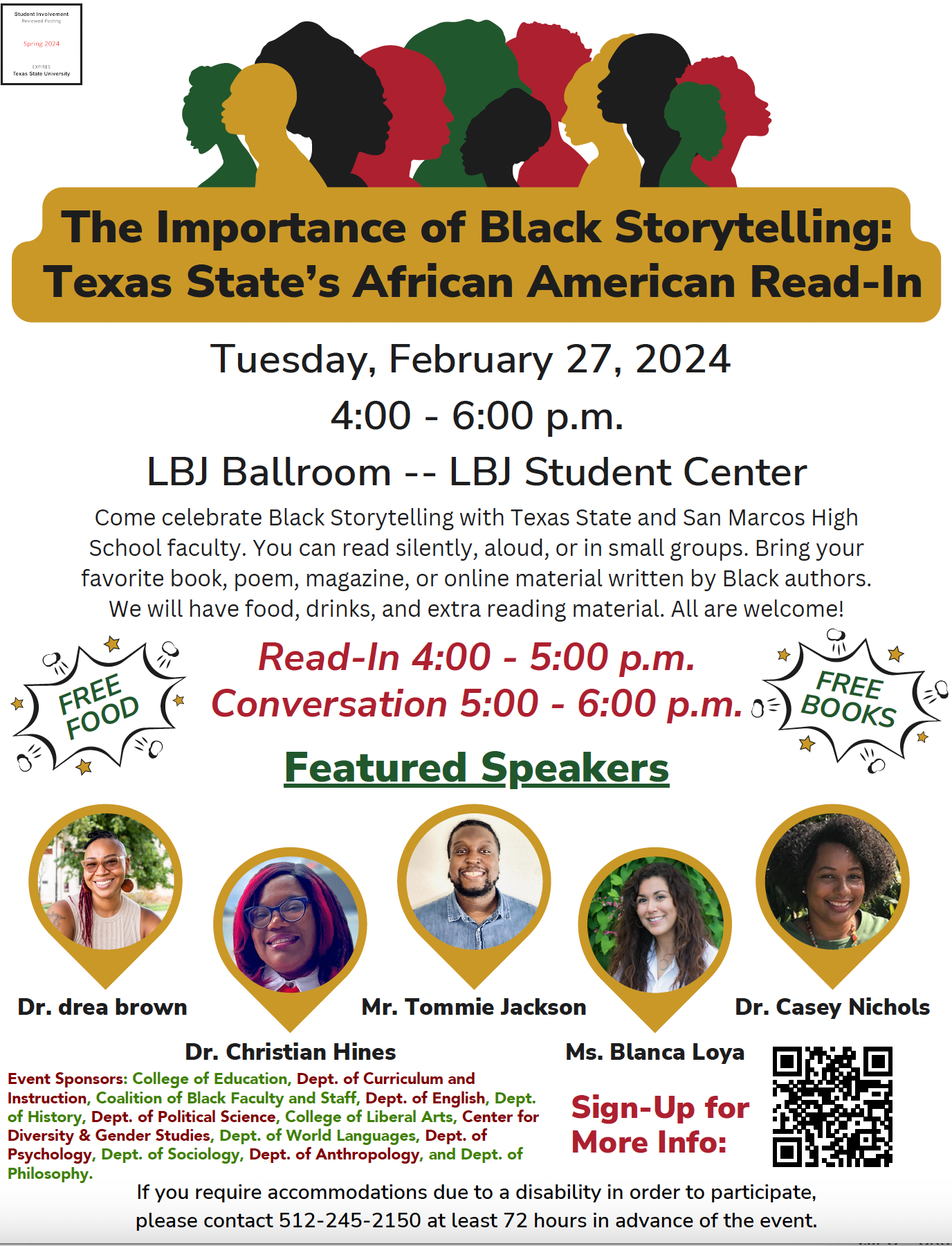

Deans Decoded: Meet Maneka Brooks

Maneka Brooks

Text shared below copied from: https://insideportlandstate.pdx.edu/2025/01/16/deans-decoded-meet-dean-maneka-brooks/

Having arrived from Texas State University this summer, Dean Maneka Brooks brings fresh perspectives and a vibrant energy to the College of Education. Her office reflects her identity and values, featuring colorful artwork that celebrates her South Asian and Black heritage, shelves lined with books that amplify linguistically and racially minoritized voices and whimsical stuffed animals with happy eyes — a nod to the joy she values in education and life. As a scholar of educational linguistics, she leads with a sharp focus on equity and is passionate about creating pathways to education for all students. Her journey from teacher to dean reflects a deep commitment to fostering inclusive spaces and preparing future educators, counselors and leaders to make meaningful change in their communities.

Inside Portland State’s Ruben Gill Herrera sat down with Dean Brooks to chat about her background and the things she’s looking forward to at the College of Education.

RGH: Can you tell us a little bit about all your office decor?

MB: My office is really important because it represents who I am — all of my different identities and all the different people in my family. One key theme in my office is the multiplicity of Blackness and the African diaspora. So, all my children’s books are written by people from different cultures including Afro-Latinos, immigrants from the continent of Africa and African Americans. And then since I’m also South Asian, my mom brought me this tapestry from Sri Lanka. I display this because I like the colors and it represents the island where she’s from. And then there’s just other things here that represent what I believe about the world, about queer and transgender people’s rights to bodily autonomy. And also just about my little sayings that I keep to remind myself, like “we don’t have to be perfect but we can exist and still do good things.”

RGH: What is the best advice you have ever received?

MB: The best advice I ever received was not to compare myself to other people — that we all have our own journey and there’s different ways of arriving at a goal. I always felt a lot of pressure to do things in lockstep, but learned that the creative way of arriving at a goal can allow you to bring a different kind of experience and a unique perspective.

RGH: Do you have a favorite item or an item here that has special meaning for you?

MB: Yes, my collection of stuffed animals. You may wonder why a dean would have a collection of stuffed animals. But I keep this here because throughout the day it’s nice to turn around and look at something that’s smiling at you — that brings you good energy. It reminds me to be silly, to stay happy and that just because you’re in a certain position, you don’t have to act a certain way. You can still be authentic to yourself. And it just reminds me of a lot of the characters that have brought me joy in other parts of my life.

RGH: What book changed your life?

MB: It’s hard to identify a particular book that changed my life, but I will say there’s a genre that I love and that’s memoir. What I love about memoir is you get to listen to someone else’s experience about their life. You get to hear about their introspection, the way they saw their world at that moment and what they think about it afterwards. I have two memoirs on my desk here that I’ve read recently and that are really interesting to me. One is Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson. The other is Heavy by Kiese Laymon.

RGH: What is your go-to karaoke song?

MB: Again, it’s hard to identify one song, but I would say my favorite songs to sing are by Paquita La Del Barrio. I like her music because I love the way that she uses language. I love the strong feminine voice, and it’s just really kind of fun and spunky.

RGH: Is there something personal you can share that not many people know about you?

MB: So one interesting fact that a lot of people don’t know about me is that I’m actually hard of hearing. And so I wear hearing aids. I think that’s something that I like to share with people because you don’t always notice that about somebody. It’s something that’s new to me and I’m learning how to navigate the world as a person who is hard of hearing. And I think it’s important to share these things with people to normalize it.

RGH: What is something you didn’t know about PSU before taking the position of dean?

MB: I didn’t realize how every building was so unique, and it kind of represents how Portland is because when you look at different buildings at Portland State, there are some that look like office buildings. There are others that just look like they were built a while ago in a cool way. And then there are some that look very modern. And so all of it together still has a very unifying feeling, but it represents how here at Portland State, we can all be ourselves, but we’re all still coming together as a whole.

RGH: What were your first impressions of Portland?

MB: What I love about Portland is how green it is and how you get the best parts of living in a city. Take this weekend for example. We went to see some of the waterfalls, and at the same time, had a really cute brunch downtown in the city. So you get the best of all worlds.

RGH: Can you talk about your journey to becoming a dean.

MB: No child wakes up one day and says, “Hey, I want to be a dean.” I was just really passionate about how we can use structures and systems to make change, to make people feel included. And as I’ve gone through my journey from being a teacher to being a professor and now to being a dean, I’ve always sought ways to be in situations, to be in rooms where I thought I could make a difference to make things better for others. And so for me, I decided to be a dean when I realized that I can be involved in making policies and working with groups to make higher education an inclusive space for people—particularly in the College of Education. I enjoy thinking about how we can enact pathways to bring more diverse people into teaching, counseling and leadership, broadly.

RGH: Your PhD is in educational linguistics. How does that connect with what you do now?

MB: My focus in educational linguistics was examining why bilingual students end up being classified as English learners, even though they speak English, and how there’s unfair practices and policies in that. The larger connecting theme that I see in all of this is how policies that are designed to do good things can actually inadvertently end up hurting people. I believe all this connects to what I do now — thinking through that systematic critical lens about the things that we do on a day-to-day basis here in the College of Education to make sure that we’re being inclusive and preparing the best teachers, leaders and counselors for Portland, for Oregon and for the broader community.

RGH: What are you most excited about?

MB: What I’m really excited about right now is thinking again about pathways to bring new students into the College of Education. I’m particularly excited about collaborating with our community college partners. One of the reasons that I came here to Portland State is because it’s an access institution. We’re committed to working with non-traditional students — students that are working full-time or that transfer from community college — as well as serving traditional students recently graduated from high school. So I’m really focused on how we can develop pathways to make sure that people can come here and continue to thrive.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity